Your roommate has a job waiting tables and gets home around midnight on Thursday nights. She often brings a couple friends from work home with her. They watch television, listen to music, or play video games and talk and laugh. You have an 8 a. Last Friday, you talked to her and asked her to keep it down in the future. Scenario 3: Sharing possessions. When you go out to eat, you often bring back leftovers to have for lunch the next day during your short break between classes. Scenario 4: Money conflicts.

7 Steps to Resolving Conflict With a Passive-Aggressive | Psychology Today

Your roommate got mono and missed two weeks of work last month. Since he has a steady job and you have some savings, you cover his portion of the rent and agree that he will pay your portion next month. The next month comes around and he informs you that he only has enough to pay his half. Scenario 5: Value and personality conflicts. You like to go out to clubs and parties and have friends over, but your roommate is much more of an introvert. One day she tells you that she wants to break the lease so she can move out early to live with one of her friends.

If you break the lease, you automatically lose your portion of the security deposit. Culture is an important context to consider when studying conflict, and recent research has called into question some of the assumptions of the five conflict management styles discussed so far, which were formulated with a Western bias. John Oetzel, Adolfo J. While there are some generalizations we can make about culture and conflict, it is better to look at more specific patterns of how interpersonal communication and conflict management are related.

We can better understand some of the cultural differences in conflict management by further examining the concept of face. Our face The projected self we desire to put into the world. Face negotiation theory Theory that argues people in all cultures negotiate face through communication encounters, and that cultural factors influence how we engage in facework, especially in conflicts.

John G. These cultural factors influence whether we are more concerned with self-face or other-face and what types of conflict management strategies we may use. One key cultural influence on face negotiation is the distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultures. The distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultures is an important dimension across which all cultures vary. Individualistic cultures Culture that emphasizes individual identity over group identity and encourages competition and self-reliance. Collectivistic cultures Culture that values in-group identity over individual identity and values conformity to social norms of the in-group.

Workplace aggression

Mararet U. Dsilva and Lisa O. However, within the larger cultures, individuals will vary in the degree to which they view themselves as part of a group or as a separate individual, which is called self-construal. Independent self-construal indicates a perception of the self as an individual with unique feelings, thoughts, and motivations.

Interdependent self-construal indicates a perception of the self as interrelated with others.

Not surprisingly, people from individualistic cultures are more likely to have higher levels of independent self-construal, and people from collectivistic cultures are more likely to have higher levels of interdependent self-construal. Self-construal and individualistic or collectivistic cultural orientations affect how people engage in facework and the conflict management styles they employ.

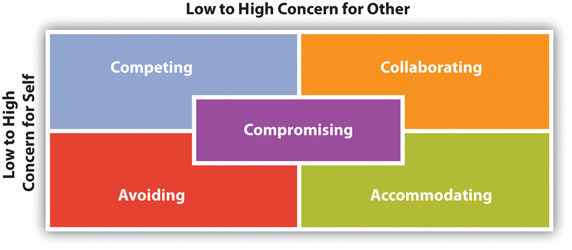

Self-construal alone does not have a direct effect on conflict style, but it does affect face concerns, with independent self-construal favoring self-face concerns and interdependent self-construal favoring other-face concerns. There are specific facework strategies for different conflict management styles, and these strategies correspond to self-face concerns or other-face concerns.

Research done on college students in Germany, Japan, China, and the United States found that those with independent self-construal were more likely to engage in competing, and those with interdependent self-construal were more likely to engage in avoiding or collaborating. And in general, this research found that members of collectivistic cultures were more likely to use the avoiding style of conflict management and less likely to use the integrating or competing styles of conflict management than were members of individualistic cultures.

The following examples bring together facework strategies, cultural orientations, and conflict management style: Someone from an individualistic culture may be more likely to engage in competing as a conflict management strategy if they are directly confronted, which may be an attempt to defend their reputation self-face concern. Someone in a collectivistic culture may be more likely to engage in avoiding or accommodating in order not to embarrass or anger the person confronting them other-face concern or out of concern that their reaction could reflect negatively on their family or cultural group other-face concern.

While these distinctions are useful for categorizing large-scale cultural patterns, it is important not to essentialize or arbitrarily group countries together, because there are measurable differences within cultures. Culture always adds layers of complexity to any communication phenomenon, but experiencing and learning from other cultures also enriches our lives and makes us more competent communicators.

Conflict is inevitable and it is not inherently negative. A key part of developing interpersonal communication competence involves being able to effectively manage the conflict you will encounter in all your relationships.

One key part of handling conflict better is to notice patterns of conflict in specific relationships and to generally have an idea of what causes you to react negatively and what your reactions usually are. Much of the research on conflict patterns has been done on couples in romantic relationships, but the concepts and findings are applicable to other relationships. Four common triggers for conflict are criticism, demand, cumulative annoyance, and rejection.

Andrew Christensen and Neil S. Comments do not have to be meant as criticism to be perceived as such. Gary, however, may take the comment personally and respond negatively back to his mom, starting a conflict that will last for the rest of his visit. Demands also frequently trigger conflict, especially if the demand is viewed as unfair or irrelevant. Tone of voice and context are important factors here. As we discussed earlier, demands are sometimes met with withdrawal rather than a verbal response.

If you are doing the demanding, remember a higher level of information exchange may make your demand clearer or more reasonable to the other person. If you are being demanded of, responding calmly and expressing your thoughts and feelings are likely more effective than withdrawing, which may escalate the conflict. Cumulative annoyance is a building of frustration or anger that occurs over time, eventually resulting in a conflict interaction.

For example, your friend shows up late to drive you to class three times in a row. Criticism and demands can also play into cumulative annoyance. We have all probably let critical or demanding comments slide, but if they continue, it becomes difficult to hold back, and most of us have a breaking point. The problem here is that all the other incidents come back to your mind as you confront the other person, which usually intensifies the conflict. A good strategy for managing cumulative annoyance is to monitor your level of annoyance and occasionally let some steam out of the pressure cooker by processing through your frustration with a third party or directly addressing what is bothering you with the source.

No one likes the feeling of rejection. Vulnerability is a component of any close relationship. When we care about someone, we verbally or nonverbally communicate. We may tell our best friend that we miss them, or plan a home-cooked meal for our partner who is working late. The vulnerability that underlies these actions comes from the possibility that our relational partner will not notice or appreciate them. When someone feels exposed or rejected, they often respond with anger to mask their hurt, which ignites a conflict.

Managing feelings of rejection is difficult because it is so personal, but controlling the impulse to assume that your relational partner is rejecting you, and engaging in communication rather than reflexive reaction, can help put things in perspective. Concepts discussed in Chapter 2 "Communication and Perception" can be useful here, as perception checking, taking inventory of your attributions, and engaging in information exchange to help determine how each person is punctuating the conflict are useful ways of managing all four of the triggers discussed.

Interpersonal conflict may take the form of serial arguing A repeated pattern of disagreement over an issue. Serial arguments do not necessarily indicate negative or troubled relationships, but any kind of patterned conflict is worth paying attention to. There are three patterns that occur with serial arguing: repeating, mutual hostility, and arguing with assurances.

The pattern may continue if the other person repeats their response to your reminder. A predictable pattern of complaint like this leads participants to view the conflict as irresolvable. The second pattern within serial arguments is mutual hostility, which occurs when the frustration of repeated conflict leads to negative emotions and increases the likelihood of verbal aggression.

Again, a predictable pattern of hostility makes the conflict seem irresolvable and may lead to relationship deterioration. Whereas the first two patterns entail an increase in pressure on the participants in the conflict, the third pattern offers some relief. If people in an interpersonal conflict offer verbal assurances of their commitment to the relationship, then the problems associated with the other two patterns of serial arguing may be ameliorated.

Even though the conflict may not be solved in the interaction, the verbal assurances of commitment imply that there is a willingness to work on solving the conflict in the future, which provides a sense of stability that can benefit the relationship. Although serial arguing is not inherently bad within a relationship, if the pattern becomes more of a vicious cycle, it can lead to alienation, polarization, and an overall toxic climate, and the problem may seem so irresolvable that people feel trapped and terminate the relationship. There are some negative, but common, conflict reactions we can monitor and try to avoid, which may also help prevent serial arguing.

Two common conflict pitfalls are one-upping and mindreading. John M. Gottman, What Predicts Divorce? One-upping Quick reaction to communication from another person that escalates conflict. Mindreading Communication in which one person attributes something to the other using generalizations, usually leading to a defensive response that escalates conflict. Remember concepts like attribution and punctuation in these moments. Nicki may have received bad news and was eager to get support from Sam when she arrived home.

- Assertive, Nonassertive, and Aggressive Behaviors | Anti-Violence Initiatives.

- What you need to do;

- beechnut fruities on the go coupons.

Mindreading leads to patterned conflict, because we wrongly presume to know what another person is thinking. Validating the person with whom you are in conflict can be an effective way to deescalate conflict.

The firewall on this server is blocking your connection.

As with all the aspects of communication competence we have discussed so far, you cannot expect that everyone you interact with will have the same knowledge of communication that you have after reading this book. But it often only takes one person with conflict management skills to make an interaction more effective. Now we turn to a discussion of negotiation steps and skills as a more structured way to manage conflict.